Labor activists didn't receive the death sentence just so you could buy a discounted mattress.

Reflections on the founding of Labor Day, child labor practices, and the costs of challenging status quos.

Squint hard enough through the haze of half-off mattress ads (how often are people buying mattresses anyway ?) and the smoke of over-charred hot dogs, and you might just catch it: Labor Day’s original spirit.

Growing up in Oregon, I was never really familiar with how unions functioned or the cultural weight behind union jobs and all they represented. The only people I knew in unions were teachers and nurses. To the modern 2025 American, Labor Day provides another excuse to go camping with hopes that the weather will be better than the last camping trip taken during the long Memorial Day Weekend bookending the first half of summer.

While the midwest might be more familiar with the Labor Movement and the significance of Labor Day, being at the epicenter of the US Industrial Revolution, the true foundation of the holiday and what it stands for often gets overlooked.

Labor Day was not established on common grounds of peace, love, and respect between the working class, Corporate America, and the federal government.

Workers before us fought and were killed trying to achieve the 5-day work week that has become our status quo.

Labor Day Origins

A holiday dedicated to working Americans, giving them one day off, was unthinkable. Until it wasn’t.

In the 1800’s, workers had no rights, and business owners of the leading industries, like the steel and railway companies, wanted to keep it that way.

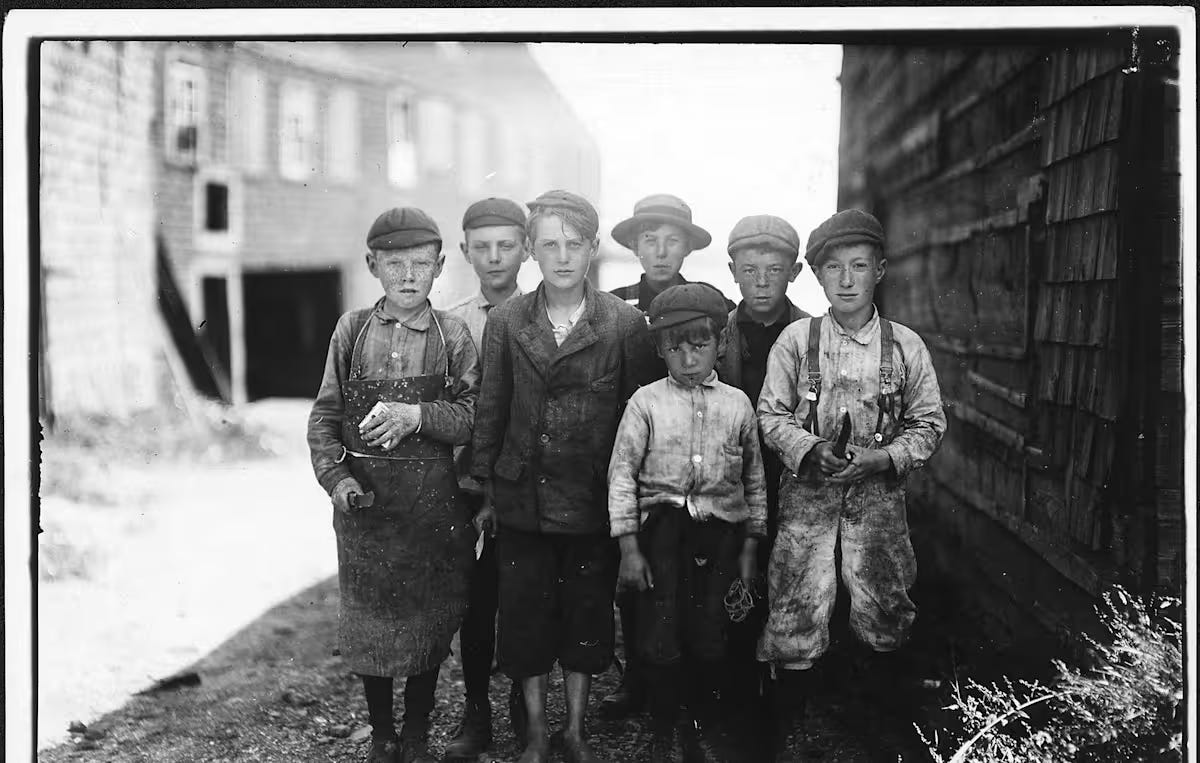

During the Industrial Revolution, the US was booming with expansion and commerce, and the average American was working 12 hours per day, 7 days a week. Children as young as 5 years old were working in factories and mines, getting paid pennies.

As American manufacturing and industrialization continued to grow, two classes began to form: the business owners, and the working class. The rich and the poor. The US was thriving in its expansion, gaining influence and global power through its manufacturing, while the working class wasn’t allowed one day off in recognition of their contributions.

During this time, trade unions started organizing. The first trade union was formed in 1794 in Philadelphia, the Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers (shoemakers). The first national labor federation wasn’t founded until 1866 - the National Labor Union. Through collective bargaining, the unions began demanding better treatment for their workers - organizing strikes and rallies to protest the maltreatment by the corporations and to push for an 8-hour workday, amongst other reforms.

In 1881, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (the predecessor to the American Federation of Labor - AFL) was created to serve as the labor’s lobbying arm in Washington, as some objectives could only be achieved through state action. The founders of the AFL operated on the notion that through self-organization and the concentration of conscious goals could they have a fight against the industrial complex.

At first, trade unionism was mainly the movement of skilled workers and didn’t have much cross over with the “unskilled” factory workers yet, often excluding people of color and women from their organizations as well. They weren’t fighting the entire system of the industrial complex, they focused on advocating for better treatment and fair wages for themselves within the current system.

One right the labor activists were fighting for was a federally recognized holiday to celebrate American workers. In 1882, Peter J. McGuire of the AFL suggested setting aside a general holiday to celebrate the laboring classes, but history also cites Alderman Matthew Maguire of New Jersey as the author of Labor Day as a holiday. Both men attended the country’s first Labor Day “celebration” in New York City that year on September 5th.

While some sources site this as the first Labor Day parade, other sources note that the parade was really a march of 10,000 workers from City Hall to Union Square, organized by the Central Labor Union. The workers took unpaid time off to march the streets of NYC. It was a celebration for change to come, but that change wouldn’t come until 12 years later, after many fights waged against employers and the federal government.

In 1887, states independently started recognizing their own worker holidays, with Oregon becoming the first state to pass a law recognizing Labor Day, and Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York following closely after.

A federal recognition of Labor Day would not be signed into law until June 28th, 1894, by President Grover Cleveland.

The Haymarket Riot (1886)

Separate from the ideologies of unionism, advocates for general laborers also became prevalent, representing a more inclusive group of people fighting for workers rights and social reform. The Knights of Labor was formed in the mid-1880’s, advocating for more broad social reform to the entire economic order, not just focusing on workplace issues. They were challenging the status quo of the entire owner-worker relationship ecosystem and wanted the industries to be worker-owned and run democratically.

The two labor groups, the unionist and the social reform activists, while later combining into shared efforts, started off as what they saw as rivals to each others missions. This is most starkly captured in the Haymarket Riot.

By the 1880s, strikes by industrial workers were increasingly common, as working conditions were dangerous and wages were low. The Labor Movement included a more radical faction made up of socialists, communists, and anarchists, the social reformers advocating for an entirely new system. Many of these labor “radicals" were German immigrants.

On May 4th, 1886, a rally was organized at the Haymarket Square in Chicago by the labor radicals. This was in protest to the fallout of events from a strike that was held the day before by workers of McCormick Reaper Works, where Chicago police open-fired on the striking workers, killing several of them. As word spread about the killings that night, another group of Chicago anarchists planned an outdoor rally to protest the police brutality. It was to take place at Haymarket Square the next day.

The rally had about 2,000 workers and activists present, with August Spies, a German immigrant anarchist leader, opening the rally with a speech. Chicago Mayor Carter Harrison was even in attendance to ensure peaceful protesting. When policemen arrived at the end of the rally to disperse the crowd, an individual (who was never identified) threw a bomb at them, killing seven officers and at least one civilian.

This was seen as a major set back to the Labor Movement and the progress made by the unionist. A nationwide xenophobia formed against foreign-born radicals and labor organizers, with police in Chicago rounding them up and convicting them on multiple offenses.

You ready for the crazy part?

Eight men were convicted as anarchists and put through, what was a labeled, a controversial trial filled with bias. The judge imposed the death sentence on seven of them, and on November 11, 1887, four of the men were hanged by the government.

Let me repeat that.

The government and judicial system HANGED. FOUR. MEN. Four men, who were fighting for workers rights.

In 1887, the US government was more willing to sentence men to the noose than to compromise on fair wages and treatment of American workers.

I understand that socialism and communism were seen as real threats against the nation at that time, and I’m not justifying throwing bombs at policemen either. But the Haymarket Riot was in protest to the blatant brutality of the Chicago police on striking workers. The workers, the same workers who were building the US from the ground up, and fighting for workers rights, were open-fired on. Activists standing up against this treatment were hanged.

The 5-day work week we value now came at a high price.

After the Haymarket Riot, socialists and labor organizers in countries around the world began celebrating May 1st as Workers Day. A federally-recognized Labor Day would still take another eight years to pass in Congress.

The Homestead Strike (1892)

The next major event in the fight for workers rights occurred in 1892 in Homestead, Pennsylvania.

Skilled workers at the steel mills in Homestead, PA had bargained exceptionally good wages and work rules for themselves, through the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers. Management of the Homestead mills became set on lowering production costs through breaking the union and lowering wages.

Andrew Carnegie, owner of the steel mills, well-known industrialist, and now-labeled “philanthropist,” and his partner Henry Frick, were making record-breaking profits. But, of course, their greed remained un-satiated (as what happens when the love of money reveals true character), and they decided to cut wages during the next union contract negotiations, which were coming to the end of their 3-year contract. Rather than negotiate, they issued ultimatums - knowing it would provoke a strike.

The union organized 8-hour shifts for picketing and protesting the actions of management. Anticipating the unrest, Frick hired the notorious Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Pinkerton was known for infiltrating unions and breaking strikes, with its workforce that was larger than the entire US Army. When the groups collided, gunfire broke out, and during the chaos the Pinkerton employees had to surrender. This left seven workers and three Pinkerton employees dead.

Four days later, the National Guard sent 8,500 forces to control the town and steel mill, per the request of Frick. By the end of the year, the Amalgamated Association had collapsed, and the workers in Homestead saw their wages shrink by one-fifth and their shifts increased from eight hours to 12.

Seven workers DIED pushing back against the wage cuts, and the US government came in to the aid of management to stifle workers and maintain status quo.

The Pullman Strikes (1894)

Unrest continued to grow among American workers and unions continued pushing for increased workers rights. This led to the Pullman Railway Strikes.

In 1893, during a nationwide economic recession, George Pullman of the Pullman Palace Car Company in Chicago reduced worker wages, laid off hundreds of workers, and fired union representatives. He also owned much of the property and commercial buildings in Pullman, Illinois where many of the workers lived, and he refused to lower rent or store prices.

On May 11, 1894, employees of the Pullman Palace Car Company walked out and went on strike to protest these actions. The following month, the American Railway Union (ARU) declared a sympathy boycott of all trains using Pullman cars, in solidarity with the strikers.

The Pullman Strike halted commerce and rail traffic in 27 states. Overwhelmed by the collective action of the strikers and the power they exercised over US commerce, the management group representing Chicago’s railroad companies sought out help from… you guessed it - the federal government.

On June 29, 1894, during a protest speech, crowd members set nearby buildings on fire and derailed a locomotive attached to a US mail train. On July 6th, the US Attorney General used the incident to ask for an injunction (a court order compelling a party, in this case the unionists, to either do or refrain from doing a specific act, like striking), and the next day, President Cleveland dispatched federal troops to the city of Chicago to enforce the injunction. This outraged Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, who wanted to prevent violence and deemed the government’s actions as unconstitutional (sounds familiar, doesn’t it…).

On cue, the Pullman Strike turned violent with the arrival of the troops. Rioters destroyed hundreds of railroad cars on July 6th, and the National Guardsmen fired into a mob on July 7th, killing 30+ people. The troops weren’t recalled until July 20th.

While the railroad workers were actively striking, Congress passed legislation in June of that year, 1894, to make Labor Day a federal legal holiday to recognize and celebrate laborers. President Cleveland signed the bill into law on June 28th - and deployed the federal troops on Chicago four days later.

It wasn’t until 1935 that the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) was signed into law, protecting the rights of most private-sector employees to organize into unions, bargain collectively with employers, and engage in other protect concerted activities. This is the act that governs most labor laws in the US to this day.

It’s… overwhelming. Looking at the history of workers rights and what activists had to sacrifice and fight for in order for us to enjoy our 8-hour work days and send kids to schools rather than the mines.

We take for granted the privileges we have as modern-day workers.

The US labor system is still far from perfect. Reflecting on the Labor Movement and the prices paid by activists before us paints a grim picture for what it’ll take to continue pushing for organizational worker reform.

I have many other thoughts on what policy (top-down) and grass-root (bottom-up), non-violent reforms could look like to ensure fair worker treatment and wages, but I’ll save those for later essays. For now, I want to bring awareness to the efforts made by Americans and global activists who came before us and to start an open conversation around labor activism.

Change doesn’t happen over night. Or without a price.

Remember - our government preferred killing people over passing laws to hold companies accountable to fair treatment of their employees. Commerce had to stop in 27 states before real problem-solving began.

Let that settle for a minute.

…

This Labor Day Weekend, amidst all the mattress shopping and hot dog grilling, I hope you take a moment to appreciate the wins Labor Day represents and to consider what challenges lie ahead for the American, and global, workforce.

Sincerely,

Grace

This article gave me a whole new appreciation for what people have sacrificed for labor rights. Thank you for this post. Wow 🤯

Crazy